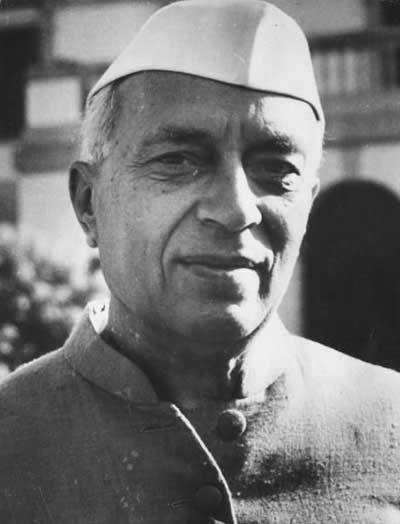

Jawaharlal Nehru

Chacha Ji

(Age 79 Yr. )

Personal Life

| Education | Law from Inner temple |

| Caste | Kashmiri Pandit |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Nationality | India |

| Profession | Barrister, Writer, Politician |

| Place | Allahabad, Uttar pradesh, India |

Physical Appearance

| Height | 5. 6 (In Feet) |

| Eye Color | Black |

| Hair Color | Grey |

Family Status

| Parents | Father- Motilal Nehru (Freedom Fighter, Lawyer, Politician) |

| Marital Status | Married |

| Spouse | Kamala Nehru (1916-1936) |

| Childern/Kids | Son- None |

| Siblings | Sister(s)- Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (First Female President of the United Nations General Assembly), Krishna Hutheesing (Writer) |

Favourite

| Food | Tandoori Chicken |

Index

Jawaharlal Nehru (14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat, statesman and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20th century. Nehru was a principal leader of the Indian nationalist movement in the 1930s and 1940s. Upon India's independence in 1947, he became the first Prime Minister of India, serving for 16 years. Nehru promoted parliamentary democracy, secularism, and science and technology during the 1950s, powerfully influencing India's arc as a modern nation. In international affairs, he steered India clear of the two blocs of the Cold War. A well-regarded author, his books written in prison, such as Letters from a Father to His Daughter (1929), Glimpses of World History (1934), An Autobiography (1936), and The Discovery of India (1946), have been read around the world. The honorific Pandit has been commonly applied before his name.

The son of Motilal Nehru, a prominent lawyer and Indian nationalist, Jawaharlal Nehru was educated in England—at Harrow School and Trinity College, Cambridge, and trained in the law at the Inner Temple. He became a barrister, returned to India, enrolled at the Allahabad High Court but never got truly interested in legal profession. Instead he gradually began to take an interest in national politics, which eventually became a full-time occupation. He joined the Indian National Congress, rose to become the leader of a progressive faction during the 1920s, and eventually of the Congress, receiving the support of Mahatma Gandhi who was to designate Nehru as his political heir. As Congress president in 1929, Nehru called for complete independence from the British Raj. Nehru and the Congress dominated Indian politics during the 1930s. Nehru promoted the idea of the secular nation-state in the 1937 Indian provincial elections, allowing the Congress to sweep the elections, and to form governments in several provinces. In September 1939, the Congress ministries resigned to protest Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's decision to join the war without consulting them. After the All India Congress Committee's Quit India Resolution of 8 August 1942, senior Congress leaders were imprisoned and for a time the organisation was crushed. Nehru, who had reluctantly heeded Gandhi's call for immediate independence, and had desired instead to support the Allied war effort during World War II, came out of a lengthy prison term to a much-altered political landscape. The Muslim League, under Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had come to dominate Muslim politics in the interim. In the 1946 provincial elections, Congress won the elections, but the League won all the seats reserved for Muslims, which the British interpreted to be a clear mandate for Pakistan in some form. Nehru became the interim prime minister of India in September 1946, with the League joining his government with some hesitancy in October 1946.

Upon India's independence on 15 August 1947, Nehru gave a critically acclaimed speech, "Tryst with Destiny"; he was sworn in as the Dominion of India's prime minister and raised the Indian flag at the Red Fort in Delhi. On 26 January 1950, when India became a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations, Nehru became the Republic of India's first prime minister. He embarked on an ambitious program of economic, social, and political reforms. Nehru promoted a pluralistic multi-party democracy. In foreign affairs, he played a leading role in establishing the Non-Aligned Movement, a group of nations that did not seek membership in the two main ideological blocs of the Cold War.

Under Nehru's leadership, the Congress emerged as a catch-all party, dominating national and state-level politics and winning elections in 1951, 1957 and 1962. Nehru remained popular with the Indian people and his premiership spanning 16 years, 286 days—which is, to date, longest in India—ended with his death on 27 May 1964 due to a heart attack.

Widely recognized as the greatest figure of modern India after Mahatma Gandhi, Nehru is also hailed as the "architect of Modern India", for his contributions in nation building, securing democracy, and preventing an ethnic civil war. His birthday is celebrated as Children's Day in India.

Early life and career (1889 to 1912)

Birth and family background

Jawaharlal Nehru was born on 14 November 1889 in Allahabad in British India. His father, Motilal Nehru (1861–1931), a self-made wealthy barrister who belonged to the Kashmiri Pandit community, served twice as president of the Indian National Congress, in 1919 and 1928. His mother, Swarup Rani Thussu (1868–1938), who came from a well-known Kashmiri Brahmin family settled in Lahore, was Motilal's second wife, his first having died in childbirth. Jawaharlal was the eldest of three children.His elder sister, Vijaya Lakshmi, later became the first female president of the United Nations General Assembly. His youngest sister, Krishna Hutheesing, became a noted writer and authored several books on her brother.

Childhood

Nehru described his childhood as a "sheltered and uneventful one". He grew up in an atmosphere of privilege at wealthy homes, including a palatial estate called the Anand Bhavan. His father had him educated at home by private governesses and tutors. Influenced by the Irish theosophist Ferdinand T. Brooks' teaching, Nehru became interested in science and theosophy.A family friend, Annie Besant subsequently initiated him into the Theosophical Society at age thirteen. However, his interest in theosophy did not prove to be enduring, and he left the society shortly after Brooks departed as his tutor. He wrote: "for nearly three years [Brooks] was with me and in many ways, he influenced me greatly".

Nehru's theosophical interests had induced him to the study of the Buddhist and Hindu scriptures. According to B. R. Nanda, these scriptures were Nehru's “first introduction to the religious and cultural heritage of [India]. ...[They] provided Nehru the initial impulse for [his] long intellectual quest which culminated…in The Discovery of India.”

Youth

Nehru became an ardent nationalist during his youth. The Second Boer War and the Russo-Japanese War intensified his feelings. Of the latter he wrote, “[The] Japanese victories [had] stirred up my enthusiasm. ...Nationalistic ideas filled my mind. I mused of Indian freedom and Asiatic freedom from the thraldom of Europe.” Later, in 1905, when he had begun his institutional schooling at Harrow, a leading school in England where he was nicknamed "Joe", G. M. Trevelyan's Garibaldi books, which he had received as prizes for academic merit, influenced him greatly. He viewed Garibaldi as a revolutionary hero. He wrote: “Visions of similar deeds in India came before, of [my] gallant fight for [Indian] freedom and in my mind, India and Italy got strangely mixed together.”

Graduation

Nehru went to Trinity College, Cambridge, in October 1907 and graduated with an honours degree in natural science in 1910. During this period, he studied politics, economics, history and literature with interest. The writings of Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, John Maynard Keynes, Bertrand Russell, Lowes Dickinson and Meredith Townsend moulded much of his political and economic thinking.

After completing his degree in 1910, Nehru moved to London and studied law at the Inner temple Inn. During this time, he continued to study Fabian Society scholars including Beatrice Webb. He was called to the Bar in 1912.

Advocate practice

After returning to India in August 1912, Nehru enrolled as an advocate of the Allahabad High Court and tried to settle down as a barrister. But, unlike his father, he had very little interest in his profession and relished neither the practice of law nor the company of lawyers: “Decidedly the atmosphere was not intellectually stimulating and a sense of the utter insipidity of life grew upon me.” His involvement in nationalist politics was to gradually replace his legal practice.

Nationalist movement (1912 to 1938)

Britain and return to India: 1912–1913

Nehru had developed an interest in Indian politics during his time in Britain as a student and a barrister. Within months of his return to India in 1912, Nehru attended an annual session of the Indian National Congress in Patna. Congress in 1912 was the party of moderates and elites, and he was disconcerted by what he saw as "very much an English-knowing upper-class affair". Nehru doubted the effectiveness of Congress but agreed to work for the party in support of the Indian civil rights movement led by Mahatma Gandhi in South Africa, collecting funds for the movement in 1913. Later, he campaigned against indentured labour and other such discrimination faced by Indians in the British colonies.

World War I: 1914–1915

When World War I broke out, sympathy in India was divided. Although educated Indians "by and large took a vicarious pleasure" in seeing the British rulers humbled, the ruling upper classes sided with the Allies. Nehru confessed he viewed the war with mixed feelings. As Frank Moraes writes, "[i]f [Nehru's] sympathy was with any country it was with France, whose culture he greatly admired". During the war, Nehru volunteered for the St. John Ambulance and worked as one of the organisation's provincial secretaries Allahabad. He also spoke out against the censorship acts passed by the British government in India.

Nehru emerged from the war years as a leader whose political views were considered radical. Although the political discourse at the time had been dominated by the moderate, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who said that it was “madness to think of independence,” Nehru had spoken, "openly of the politics of non-cooperation, of the need of resigning from honorary positions under the government and of not continuing the futile politics of representation". He ridiculed the Indian Civil Service for supporting British policies. He noted someone had once defined the Indian Civil Service, "with which we are unfortunately still afflicted in this country, as neither Indian, nor civil, nor a service". Motilal Nehru, a prominent moderate leader, acknowledged the limits of constitutional agitation, but counselled his son that there was no other "practical alternative" to it. Nehru, however, was dissatisfied with the pace of the national movement. He became involved with aggressive nationalists leaders demanding Home Rule for Indians.

The influence of moderates on Congress' politics waned after Gokhale died in 1915. Anti-moderate leaders like Annie Besant and Bal Gangadhar Tilak took the opportunity to call for a national movement for Home Rule. However, in 1915, the proposal was rejected because of the reluctance of the moderates to commit to such a radical course of action.

Nationalist movement (1939 to 1947)

When World War II began, Viceroy Linlithgow had unilaterally declared India a belligerent on the side of Britain, without consulting the elected Indian representatives. Nehru hurried back from a visit to China, announcing that, in a conflict between democracy and fascism, "our sympathies must inevitably be on the side of democracy, ... I should like India to play its full part and throw all her resources into the struggle for a new order".

After much deliberation, the Congress under Nehru informed the government that it would co-operate with the British but on certain conditions. First, Britain must give an assurance of full independence for India after the war and allow the election of a constituent assembly to frame a new constitution; second, although the Indian armed forces would remain under the British Commander-in-chief, Indians must be included immediately in the central government and given a chance to share power and responsibility. When Nehru presented Lord Linlithgow with these demands, he chose to reject them. A deadlock was reached: "The same old game is played again," Nehru wrote bitterly to Gandhi, "the background is the same, the various epithets are the same and the actors are the same and the results must be the same".

On 23 October 1939, the Congress condemned the Viceroy's attitude and called upon the Congress ministries in the various provinces to resign in protest. Before this crucial announcement, Nehru urged Jinnah and the Muslim League to join the protest, but Jinnah declined.

As Nehru had firmly placed India on the path of democracy and freedom at a time when the world was under the threat of Fascism, he and Bose split in the late 1930s when the latter agreed to seek the help of Fascists in driving the British out of India. At the same time, Nehru had supported the Republicans who were fighting against Francisco Franco's forces in the Spanish Civil War. Nehru and his aide V. K. Krishna Menon visited Spain and declared support for the Republicans. When Benito Mussolini, dictator of Italy, expressed his desire to meet, Nehru refused him.

Civil disobedience, Lahore Resolution, August Offer: 1940

In March 1940, Muhammad Ali Jinnah passed what came to be known as the Pakistan Resolution, declaring that, "Muslims are a nation according to any definition of a nation, and they must have their homelands, their territory and their State." This state was to be known as Pakistan, meaning 'Land of the Pure'. Nehru angrily declared that "all the old problems pale into insignificance before the latest stand taken by the Muslim League leader in Lahore". Linlithgow made Nehru an offer on 8 October 1940, which stated that Dominion status for India was the objective of the British government. However, it referred neither to a date nor a method to accomplish this. Only Jinnah received something more precise: "The British would not contemplate transferring power to a Congress-dominated national government, the authority of which was denied by various elements in India's national life".

In October 1940, Gandhi and Nehru, abandoning their original stand of supporting Britain, decided to launch a limited civil disobedience campaign in which leading advocates of Indian independence were selected to participate one by one. Nehru was arrested and sentenced to four years' imprisonment. On 15 January 1941, Gandhi had stated:

First term as Prime Minister: 1952 to1957

State reorganisation

In December 1953, Nehru appointed the States Reorganisation Commission to prepare for the creation of states on linguistic lines. Headed by Justice Fazal Ali, the commission itself was also known as the Fazal Ali Commission. Govind Ballabh Pant, who served as Nehru's home minister from December 1954, oversaw the commission's efforts. The commission created a report in 1955 recommending the reorganisation of India's states.

Under the Seventh Amendment, the existing distinction between Part A, Part B, Part C, and Part D states was abolished. The distinction between Part A and Part B states was removed, becoming known simply as states'. A new type of entity, the union territory, replaced the classification as a Part C or Part D state. Nehru stressed commonality among Indians and promoted pan-Indianism, refusing to reorganise states on either religious or ethnic lines.

Subsequent elections: 1957, 1962

In the 1957 elections, Under the leadership of Nehru, the Indian National Congress easily won a second term in power, taking 371 of the 494 seats. They gained an extra seven seats (the size of the Lok Sabha had been increased by five) and their vote share increased from 45.0% to 47.8%. The INC won nearly five times more votes than the Communist Party, the second largest party.

In 1962, Nehru led the Congress to victory with a diminished majority. The numbers who voted for Communist and socialist parties grew, although some right-wing groups like Bharatiya Jana Sangh also did well.

1961 annexation of Goa

After years of failed negotiations, Nehru authorised the Indian Army to invade Portuguese-controlled Portuguese India (Goa) in 1961, and then he formally annexed it to India. It increased his popularity in India, but he was criticised by the communist opposition in India for the use of military force.

Sino-Indian War of 1962

From 1959, in a process that accelerated in 1961, Nehru adopted the "Forward Policy" of setting up military outposts in disputed areas of the Sino-Indian border, including in 43 outposts in territory not previously controlled by India. China attacked some of these outposts, and the Sino-Indian War began, which India lost. The war ended with China announcing a unilateral ceasefire and with its forces withdrawing to 20 kilometers behind the line of actual control of 1959.

The war exposed the unpreparedness of India's military, which could send only 14,000 troops to the war zone in opposition to the much larger Chinese Army, and Nehru was widely criticised for his government's insufficient attention to defence. In response, defence minister V. K. Krishna Menon had resigned and Nehru sought US military aid. Nehru's improved relations with the US under John F. Kennedy proved useful during the war, as in 1962, the president of Pakistan (then closely aligned with the Americans) Ayub Khan was made to guarantee his neutrality regarding India, threatened by "communist aggression from Red China". India's relationship with the Soviet Union, criticised by right-wing groups supporting free-market policies, was also seemingly validated. Nehru would continue to maintain his commitment to the non-aligned movement, despite calls from some to settle down on one permanent ally.

The aftermath of the war saw sweeping changes in the Indian military to prepare it for similar conflicts in the future and placed pressure on Nehru, who was seen as responsible for failing to anticipate the Chinese attack on India. Under American advice (by American envoy John Kenneth Galbraith who made and ran American policy on the war as all other top policymakers in the US were absorbed in the coincident Cuban Missile Crisis) Nehru refrained from using the Indian air force to beat back the Chinese advances. The CIA later revealed that, at that time, the Chinese had neither the fuel nor runways long enough to use their air force effectively in Tibet. Indians, in general, became highly sceptical of China and its military. Many Indians view the war as a betrayal of India's attempts at establishing a long-standing peace with China and started to question Nehru's usage of the term Hindi-Chini bhai-bhai (Indians and Chinese are brothers). The war also put an end to Nehru's earlier hopes that India and China would form a strong Asian Axis to counteract the increasing influence of the Cold War bloc superpowers.

The unpreparedness of the army was blamed on Defence Minister Menon, who "resigned" his government post to allow for someone who might modernise India's military further. India's policy of weaponisation using indigenous sources and self-sufficiency began in earnest under Nehru, completed by his daughter Indira Gandhi, who later led India to a crushing military victory over rival Pakistan in 1971. Toward the end of the war, India had increased her support for Tibetan refugees and revolutionaries, some of them having settled in India, as they were fighting the same common enemy in the region. Nehru ordered the raising of an elite Indian-trained "Tibetan Armed Force" composed of Tibetan refugees, which served with distinction in future wars against Pakistan in 1965 and 1971.

During the conflict, Nehru wrote two urgent letters to US President John F. Kennedy, requesting 12 squadrons of fighter jets and a modern radar system. These jets were seen as necessary to increase Indian air strength so that air-to-air combat could be initiated safely from the Indian perspective (bombing troops was seen as unwise for fear of Chinese retaliatory action). Nehru also asked that these aircraft be manned by American pilots until Indian airmen were trained to replace them. The Kennedy Administration (which was involved in the Cuban Missile Crisis during most of the Sino-Indian War) rejected these requests, leading to a cooling of Indo-US relations. According to former Indian diplomat G Parthasarathy, "only after we got nothing from the US did arms supplies from the Soviet Union to India commence". According to Time magazine's 1962 editorial on the war, however, this may not have been the case. The editorial states,

Vision and governing policies

According to Bhikhu Parekh, Nehru can be regarded as the founder of the modern Indian state. Parekh attributes this to the national philosophy Nehru formulated for India. For him, modernisation was the national philosophy, with seven goals: national unity, parliamentary democracy, industrialisation, socialism, development of the scientific temper, and non-alignment. In Parekh's opinion, the philosophy and the policies that resulted from this benefited a large section of society such as public sector workers, industrial houses, middle and upper peasantry. However, it failed to benefit the urban and rural poor, the unemployed and the Hindu fundamentalists.

After the exit of Subhash Chandra Bose from mainstream Indian politics (because of his support of violence in driving the British out of India), the power struggle between the socialists and conservatives in the Congress party balanced out. However, the death of Vallabhbhai Patel in 1950 left Nehru as the sole remaining iconic national leader, and soon the situation became such that Nehru could implement many of his basic policies without hindrance Nehru's daughter, Indira Gandhi, was able to fulfil her father's dream by the 42nd amendment (1976) of the Indian constitution by which India officially became "socialist" and "secular", during the state of emergency she imposed.

Economic policies

Nehru implemented policies based on import substitution industrialisation and advocated a mixed economy where the government-controlled public sector would co-exist with the private sector. He believed the establishment of basic and heavy industry was fundamental to the development and modernisation of the Indian economy. The government, therefore, directed investment primarily into key public sector industries—steel, iron, coal, and power—promoting their development with subsidies and protectionist policies.

The policy of non-alignment during the Cold War meant that Nehru received financial and technical support from both power blocs in building India's industrial base from scratch. Steel mill complexes were built at Bokaro and Rourkela with assistance from the Soviet Union and West Germany. There was substantial industrial development. Industry grew 7.0% annually between 1950 and 1965—almost trebling industrial output and making India the world's seventh largest industrial country. Nehru's critics, however, contended that India's import substitution industrialisation, which was continued long after the Nehru era, weakened the international competitiveness of its manufacturing industries. India's share of world trade fell from 1.4% in 1951–1960 to 0.5% between 1981 and 1990. However, India's export performance is argued to have showed actual sustained improvement over the period. The volume of exports grew at an annual rate of 2.9% in 1951–1960 to 7.6% in 1971–1980.

GDP and GNP grew 3.9 and 4.0% annually between 1950 and 1951 and 1964–1965. It was a radical break from the British colonial period, but the growth rates were considered anaemic at best compared to other industrial powers in Europe and East Asia. India lagged behind the miracle economies (Japan, West Germany, France, and Italy). State planning, controls, and regulations were argued to have impaired economic growth. While India's economy grew faster than both the United Kingdom and the United States, low initial income and rapid population increase meant that growth was inadequate for any sort of catch-up with rich income nations.

Nehru's preference for big state-controlled enterprises created a complex system of quantitative regulations, quotas and tariffs, industrial licenses, and a host of other controls. This system, known in India as Licence Raj, was responsible for economic inefficiencies that stifled entrepreneurship and checked economic growth for decades until the liberalisation policies initiated by the Congress government in 1991 under P. V. Narasimha Rao.

Agriculture policies

Under Nehru's leadership, the government attempted to develop India quickly by embarking on agrarian reform and rapid industrialisation. A successful land reform was introduced that abolished giant landholdings, but efforts to redistribute land by placing limits on landownership failed. Attempts to introduce large-scale cooperative farming were frustrated by landowning rural elites, who formed the core of the powerful right-wing of the Congress and had considerable political support in opposing Nehru's efforts. Agricultural production expanded until the early 1960s, as additional land was brought under cultivation and some irrigation projects began to have an effect. The establishment of agricultural universities, modelled after land-grant colleges in the United States, contributed to the development of the economy. These universities worked with high-yielding varieties of wheat and rice, initially developed in Mexico and the Philippines, that in the 1960s began the Green Revolution, an effort to diversify and increase crop production. At the same time, a series of failed monsoons would cause serious food shortages, despite the steady progress and an increase in agricultural production.

Social policies

Education

Nehru was a passionate advocate of education for India's children and youth, believing it essential for India's future progress. His government oversaw the establishment of many institutions of higher learning, including the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, the Indian Institutes of Technology, the Indian Institutes of Management and the National Institutes of Technology. Nehru also outlined a commitment in his five-year plans to guarantee free and compulsory primary education to all of India's children. For this purpose, Nehru oversaw the creation of mass village enrolment programs and the construction of thousands of schools. Nehru also launched initiatives such as the provision of free milk and meals to children to fight malnutrition. Adult education centres, vocational and technical schools were also organised for adults, especially in the rural areas.

Hindu marriage law

Under Nehru, the Indian Parliament enacted many changes to Hindu law to criminalise caste discrimination and increase the legal rights and social freedoms of women.

Nehru specifically wrote Article 44 of the Indian constitution under the Directive Principles of State Policy which states: "The State shall endeavor to secure for the citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India." The article has formed the basis of secularism in India.[216] However, Nehru has been criticised for the inconsistent application of the law. Most notably, he allowed Muslims to keep their personal law in matters relating to marriage and inheritance. In the small state of Goa, a civil code based on the old Portuguese Family Laws was allowed to continue, and Nehru prohibited Muslim personal law. This resulted from the annexation of Goa in 1961 by India, when Nehru promised the people that their laws would be left intact. This has led to accusations of selective secularism.

While Nehru exempted Muslim law from legislation and they remained unreformed, he passed the Special Marriage Act in 1954. The idea behind this act was to give everyone in India the ability to marry outside the personal law under a civil marriage. The law applied to all of India, except Jammu and Kashmir, again leading to accusations of selective secularism. In many respects, the act was almost identical to the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, demonstrates how secularised the law regarding Hindus had become. The Special Marriage Act allowed Muslims to marry under it and keep the protections, generally beneficial to Muslim women, that could not be found in the personal law. Under the act, polygamy was illegal, and inheritance and succession would be governed by the Indian Succession Act, rather than the respective Muslim personal law. Divorce would be governed by the secular law, and maintenance of a divorced wife would be along the lines set down in the civil law.

Death

Nehru's health began declining steadily in 1962. In the spring of 1962, he was affected with viral infection over which he spent most of April in bed. In the next year, through 1963, he spent months recuperating in Kashmir. Some writers attribute this dramatic decline to his surprise and chagrin over the Sino-Indian War, which he perceived as a betrayal of trust. Upon his return from Dehradun on 26 May 1964, he was feeling quite comfortable and went to bed at about 23:30 as usual. He had a restful night until about 06:30. Soon after he returned from the bathroom, Nehru complained of pain in the back. He spoke to the doctors who attended on him for a brief while, and almost immediately he collapsed. He remained unconscious until he died at 13:44. His death was announced in the Lok Sabha at 14:00 local time on 27 May 1964; the cause of death was believed to be a heart attack. Draped in the Indian national Tri-colour flag, the body of Jawaharlal Nehru was placed for public viewing. "Raghupati Raghava Rajaram" was chanted as the body was placed on the platform. On 28 May, Nehru was cremated in accordance with Hindu rites at the Shantivan on the banks of the Yamuna, witnessed by 1.5 million mourners who had flocked into the streets of Delhi and the cremation grounds.

US President Lyndon B. Johnson remarked on his death:-

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev remarked:-

Nehru's death left India with no clear political heir to his leadership. Lal Bahadur Shastri later succeeded Nehru as the prime minister.

The death was announced to the Indian parliament in words similar to Nehru's own at the time of Gandhi's assassination: “The light is out.” India's future prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee famously delivered Nehru an acclaimed eulogy. He hailed Nehru as Bharat Mata's "favourite prince" and likened him to the Hindu god Rama.