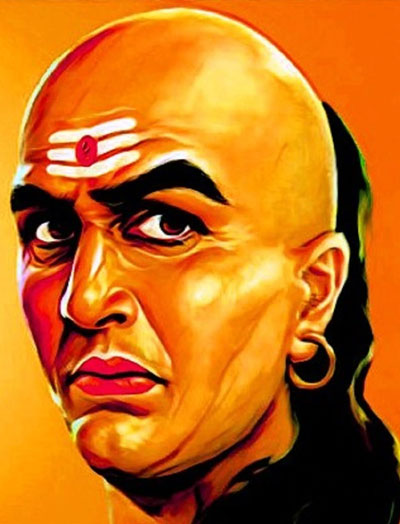

Chanakya

Chanakya

Personal Life

| Education | Studied Sociology, Politics, Economics, Philosophy |

| Caste | Brahmin |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Profession | Teacher, Philosopher, Economist, Jurist and Royal Advisor |

| Place | Takshashila, |

Physical Appearance

| Eye Color | Black |

Family

| Parents | Father- Rishi Canak or Chanin |

Index

| 1. Background |

| 2. Jain version |

| 3. Buddhist version |

| 4. Kashmiri version |

| 5. Mudrarakshasa version |

| 6. Literary works |

| 7. Legacy |

| 8. Chanakyan vocabulary |

| 9. In popular culture |

Chanakya was an ancient Indian polymath who was active as a teacher, author, strategist, philosopher, economist, jurist, and royal advisor. He is traditionally identified as Kauṭilya or Vishnugupta, who authored the ancient Indian political treatise, the Arthashastra, a text dated to roughly between the fourth century BCE and the third century CE. As such, he is considered the pioneer of the field of political science and economics in India, and his work is thought of as an important precursor to classical economics. His works were lost near the end of the Gupta Empire in the sixth century CE and not rediscovered until the early 20th century. Around 321 BCE, Chanakya assisted the first Mauryan emperor Chandragupta in his rise to power and is widely credited for having played an important role in the establishment of the Maurya Empire. Chanakya served as the chief advisor to both emperors Chandragupta and his son Bindusara.

Background

Sources of information

There is little documented historical information about Chanakya: most of what is known about him comes from semi-legendary accounts. Thomas Trautmann identifies four distinct accounts of the ancient Chanakya-Chandragupta katha (legend):

| Version of the legend | Example texts |

|---|---|

| Buddhist version | Mahavamsa and its commentary Vamsatthappakasini (Pali language) |

| Jain version | Parishishtaparvan by Hemachandra |

| Kashmiri version | Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva, Brihat-Katha-Manjari by Ksemendra |

| Vishakhadatta's version | Mudrarakshasa, a Sanskrit play by Vishakhadatta |

In all the four versions, Chanakya feels insulted by the Nanda king, and vows to destroy him. After dethroning the Nanda, he installs Chandragupta as the new king.

Buddhist version

The legend of Chanakya and Chandragupta is detailed in the Pali-language Buddhist chronicles of Sri Lanka. It is not mentioned in Dipavamsa, the oldest of these chronicles. The earliest Buddhist source to mention the legend is Mahavamsa, which is generally dated between fifth and sixth centuries CE. Vamsatthappakasini (also known as Mahvamsa Tika), a commentary on Mahavamsa, provides some more details about the legend. Its author is unknown, and it is dated variously from sixth century CE to 13th century CE. Some other texts provide additional details about the legend; for example, the Maha-Bodhi-Vamsa and the Atthakatha give the names of the nine Nanda kings said to have preceded Chandragupta.

Jain version

The Chandragupta-Chanakya legend is mentioned in several commentaries of the Shvetambara canon. The most well-known version of the Jain legend is contained in the Sthaviravali-Charita or Parishishta-Parvan, written by the 12th-century writer Hemachandra. Hemachandra's account is based on the Prakrit kathanaka literature (legends and anecdotes) composed between the late first century CE and mid-8th century CE. These legends are contained in the commentaries (churnis and tikas) on canonical texts such as Uttaradhyayana and Avashyaka Niryukti.

Thomas Trautmann believes that the Jain version is older and more consistent than the Buddhist version of the legend.

Kashmiri version

Brihatkatha-Manjari by Kshemendra and Kathasaritsagara by Somadeva are two 11th-century Kashmiri Sanskrit collections of legends. Both are based on a now-lost Prakrit-language Brihatkatha-Sarit-Sagara, which was based on the now-lost Paishachi-language Brihatkatha by Gunadhya. The Chanakya-Chandragupta legend in these collections features another character, named Shakatala (IAST: Śakaṭāla).

Mudrarakshasa version

Mudrarakshasa ("The signet ring of Rakshasa") is a Sanskrit play by Vishakhadatta. Its date is uncertain, but it mentions the Huna, who invaded northern India during the Gupta period. Therefore, it could not have been composed before the Gupta era. It is dated variously from the late fourth century to the eighth century. The Mudrarakshasa legend contains narratives not found in other versions of the Chanakya-Chandragupta legend. Because of this difference, Trautmann suggests that most of it is fictional or legendary, without any historical basis.

Identification with Kauṭilya or Vishnugupta

The ancient Arthashastra has been traditionally attributed to Chanakya by a number of scholars. The Arthashastra identifies its author as Kauṭilya, a gotra or clan name, except for one verse that refers to him by the personal name of Vishnugupta. Kauṭilya is presumably the name of the author's gotra (clan). One of the earliest Sanskrit literatures to identify Chanakya with Vishnugupta explicitly was the Panchatantra.

K. C. Ojha proposes that the traditional identification of Vishnugupta with Kauṭilya was caused by a confusion of the text's editor and its originator. He suggests that Vishnugupta was a redactor of the original work of Kauṭilya. Thomas Burrow suggests that Chanakya and Kauṭilya may have been two different people.

Jain version

According to the Jain account, Chanakya was born to two lay Jains (shravaka) named Chanin and Chaneshvari. His birthplace was the Chanaka village in Golla vishaya (region). The identity of "Golla" is not certain, but Hemachandra states that Chanakya was a Dramila, implying that he was a native of South India.

Chanakya was born with a full set of teeth. According to the monks, this was a sign that he would become a king in the future. Chanin did not want his son to become haughty, so he broke Chanakya's teeth. The monks prophesied that the baby would go on to become a power behind the throne. Chanakya grew up to be a learned shravaka, and married a Brahmin woman. Her relatives mocked her for being married to a poor man. This motivated Chanakya to visit Pataliputra, and seek donations from the king Nanda, who was famous for his generosity towards Brahmins. While waiting for the king at the royal court, Chanakya sat on the king's throne. A dasi (servant girl) courteously offered Chanakya the next seat, but Chanakya kept his kamandal (water pot) on it, while remaining seated on the throne. The servant offered him a choice of four more seats, but each time, he kept his various items on the seats, refusing to budge from the throne. Finally, the annoyed servant kicked him off the throne. Enraged, Chanakya vowed to uproot Nanda and his entire establishment, like "a great wind uproots a tree".

Buddhist version

According to the Buddhist legend, the Nanda kings who preceded Chandragupta were robbers-turned-rulers. Chanakya (IAST: Cāṇakka in Mahavamsa) was a Brahmin from Takkāsila (Takshashila). He was well-versed in three Vedas and politics. He was born with canine teeth, which were believed to be a mark of royalty. His mother feared that he would neglect her after becoming a king. To pacify her, Chanakya broke his teeth.

Chanakya had an ugly appearance, accentuated by his broken teeth and crooked feet. One day, the king Dhana Nanda organized an alms-giving ceremony for Brahmins. Chanakya went to Pupphapura (Pushpapura) to attend this ceremony. Disgusted by his appearance, the king ordered him to be thrown out of the assembly. Chanakya broke his sacred thread in anger, and cursed the king. The king ordered his arrest, but Chanakya escaped in the disguise of an Ājīvika. He befriended Dhananada's son Pabbata, and instigated him to seize the throne. With help of a signet ring given by the prince, Chanakya fled the palace through a secret door.

Chanakya escaped to the Vinjha forest. There, he made 800 million gold coins (kahapanas), using a secret technique that allowed him to turn 1 coin into 8 coins. After hiding this money, he started searching for a person worthy of replacing Dhana Nanda. One day, he saw a group of children playing: the young Chandragupta (called Chandagutta in Mahavamsa) played the role of a king, while other boys pretended to be vassals, ministers, or robbers. The "robbers" were brought before Chandragupta, who ordered their limbs to be cut off, but then miraculously re-attached them. Chandragupta had been born in a royal family, but was brought up by a hunter after his father was killed by an usurper, and the devatas caused his mother to abandon him. Astonished by the boy's miraculous powers, Chanakya paid 1000 gold coins to his foster-father, and took Chandragupta away, promising to teach him a trade.

Kashmiri version

The Kashmiri version of the legend goes like this: Vararuchi (identified with Katyayana), Indradatta and Vyadi were three disciples of the sage Varsha. Once, on behalf of their guru Varsha, they travelled to Ayodhya to seek a gurudakshina (guru's fee) from king Nanda. As they arrived to meet Nanda, the king died. Using his yogic powers, Indradatta entered Nanda's body and granted Vararuchi's request for 10 million dinars (gold coins). The royal minister Shakatala realized what was happening, and had Indradatta's body burnt. But before he could take any action against the fake king (Indradatta in Nanda's body, also called Yogananda), the king had him arrested. Shakatala and his 100 sons were imprisoned and were given food sufficient only for one person. Shakatala's 100 sons starved to death, so that their father could live to take revenge.

Meanwhile, the fake king appointed Vararuchi as his minister. As the king's character kept deteriorating, a disgusted Vararuchi retired to a forest as an ascetic. Shakatala was then restored as the minister, but kept planning his revenge. One day, Shakatala came across Chanakya, a Brahmin who was uprooting all the grass in his path, because one blade of the grass had pricked his foot. Shakatala realized that he could use a man so vengeful to destroy the fake king. He invited Chanakya to the king's assembly, promising him 100,000 gold coins for presiding over a ritual ceremony.

Shakatala hosted Chanakya in his own house and treated him with great respect. But the day Chanakya arrived at the king's court, Shakatala got another Brahmin named Subandhu to preside over the ceremony. Chanakya felt insulted, but Shakatala blamed the king for this dishonour. Chanakya then untied his topknot (sikha), and vowed not to re-tie it until the king was destroyed. The king ordered his arrest, but he escaped to Shakatala's house. There, using materials supplied by Shakatala, he performed a magic ritual which made the king sick. The king died of a fever after 7 days.

Mudrarakshasa version

According to the Mudrarakshasa version, the king Nanda once removed Chanakya from the "first seat of the kingdom" (this possibly refers to Chanakya's expulsion from the king's assembly). For this reason, Chanakya vowed not to tie his top knot (shikha) until the complete destruction of Nanda. Chanakya made a plan to dethrone Nanda, and replace him with Chandragupta, his son by a lesser queen. Chanakya engineered Chandragupta's alliance with another powerful king Parvateshvara (or Parvata), and the two rulers agreed to divide Nanda's territory after subjugating him. Their allied army included Bahlika, Kirata, Parasika, Kamboja, Shaka, and Yavana soldiers. The army invaded Pataliputra (Kusumapura) and defeated the Nandas. Parvata is identified with King Porus by some scholars.

Nanda's prime minister Rakshasa escaped Pataliputra, and continued resisting the invaders. He sent a vishakanya (poison girl) to assassinate Chandragupta. Chanakya had this girl assassinate Parvata instead, with the blame going to Rakshasa. However, Parvata's son Malayaketu learned the truth about his father's death and defected to Rakshasa's camp. Chanakya's spy Bhagurayana accompanied Malayaketu, pretending to be his friend.

Rakshasa continued to plot Chandragupta's death, but all his plans were foiled by Chanakya. For example, once Rakshasa arranged for assassins to be transported to Chandragupta's bedroom via a tunnel. Chanakya became aware of them by noticing a trail of ants carrying the leftovers of their food. He then arranged for the assassins to be burned to death.

Meanwhile, Parvata's brother Vairodhaka became the ruler of his kingdom. Chanakya convinced him that Rakshasa was responsible for killing his brother, and agreed to share half of Nanda's kingdom with him. Secretly, however, Chanakya hatched a plan to get Vairodhaka killed. He knew that the chief architect of Pataliputra was a Rakshasa loyalist. He asked this architect to build a triumphal arch for Chandragupta's procession to the royal palace. He arranged the procession to be held at midnight citing astrological reasons, but actually to ensure poor visibility. He then invited Vairodhaka to lead the procession on Chandragupta's elephant, and accompanied by Chandragupta's bodyguards. As expected, Rakshasa's loyalists arranged for the arch to fall on who they thought was Chandragupta. Vairodhaka was killed, and once again, the assassination was blamed on Rakshasa.

Literary works

Two books are attributed to Chanakya: Arthashastra, and Chanakya Niti, also known as Chanakya Neeti-shastra. The Arthashastra was discovered in 1905 by librarian Rudrapatna Shamasastry in an uncatalogued group of ancient palm-leaf manuscripts donated by an unknown pandit to the Oriental Research Institute Mysore.

The Arthashastra, which discusses monetary and fiscal policies, welfare, international relations, and war strategies in detail. The text also outlines the duties of a ruler. Some scholars believe that Arthashastra is actually a compilation of a number of earlier texts written by various authors, and Chanakya might have been one of these authors.

Chanakya Niti, which is a collection of aphorisms, said to be selected by Chanakya from the various shastras.

Legacy

Chanakya is regarded as a great thinker and diplomat in India. Many Indian nationalists regard him as one of the earliest people who envisioned a united India spanning the entire subcontinent. India's former National Security Advisor Shiv Shankar Menon praised Chanakya's Arthashastra for its precise and timeless descriptions of power. Furthermore, he recommended reading of the book for broadening the vision on strategic issues.

The diplomatic enclave in New Delhi is named Chanakyapuri in honour of Chanakya. Institutes named after him include Training Ship Chanakya, Chanakya National Law University and Chanakya Institute of Public Leadership. Chanakya circle in Mysore has been named after him.

Chanakyan vocabulary

Chanakya uses different terms to describe war other than dharma-yuddha, such as kutayudhha.

In popular culture

Plays

Several modern adaptations of the legend of Chanakya narrate his story in a semi-fictional form, extending these legends. In Chandragupta (1911), a play by Dwijendralal Ray, the Nanda king exiles his half-brother Chandragupta, who joins the army of Alexander the Great. Later, with help from Chanakya and Katyayan (the former Prime Minister of Magadha), Chandragupta defeats Nanda, who is put to death by Chanakya.

Film and television

The story of Chanakya and Chandragupta was portrayed in the 1977 Telugu film entitled Chanakya Chandragupta. Akkineni Nageswara Rao played the role of Chanakya, while N. T. Rama Rao portrayed as Chandragupta.

The 1991 TV series Chanakya is an archetypal account of the life and times of Chanakya, based on the Mudrarakshasa. The titular role of the same name was portrayed by Chandraprakash Dwivedi

Chandragupta Maurya, a 2011 TV series on NDTV Imagine is a biographical series on the life of Chandragupta Maurya and Chanakya, and is produced by Sagar Arts. Manish Wadhwa portrays the character of Chanakya in this series.

The 2015 Colors TV drama, Chakravartin Ashoka Samrat, features Chanakya during the reign of Chandragupta's son, Bindusara.

Chanakya was played by Chetan Pandit and Tarun Khanna, in the historical-drama television series Porus in 2017–2018.

Chanakya was played by Tarun Khanna, in the historical drama TV series Chandragupta Maurya in 2018–2019.

Books and academia

An English-language book titled Chanakya on Management contains 216 sutras on raja-neeti, each of which has been translated and commented upon.

A book written by Ratan Lal Basu and Rajkumar Sen deals with the economic concepts mentioned in Arthashastra and their relevance for the modern world.

Chanakya (2001) by B. K. Chaturvedi

In 2009, many eminent experts discussed the various aspects of Kauṭilya's thought in an International Conference held at the Oriental Research Institute in Mysore (India) to celebrate the centenary of discovery of the manuscript of the Arthashastra by R. Shamasastry. Most of the papers presented in the Conference have been compiled in an edited volume by Raj Kumar Sen and Ratan Lal Basu.

Chanakya's Chant by Ashwin Sanghi is a fictional account of Chanakya's life as a political strategist in ancient India. The novel relates two parallel stories, the first of Chanakya and his machinations to bring Chandragupta Maurya to the throne of Magadha; the second, that of a modern-day character called Gangasagar Mishra who makes it his ambition to position a slum child as Prime Minister of India.

The Emperor's Riddles by Satyarth Nayak features popular episodes from Chanakya's life.

Kauṭilya's role in the formation of the Maurya Empire is the essence of a historical/spiritual novel Courtesan and the Sadhu by Mysore N. Prakash.

Chanakya's contribution to the cultural heritage of Bharat (in Kannada) by Shatavadhani Ganesh with the title Bharatada Samskrutige Chanakyana Kodugegalu.

Pavan Choudary (2 February 2009). Chanakya's Political Wisdom. Wisdom Village Publications Division. ISBN 978-81-906555-0-7., a political commentary on Chanakya

Sihag, Balbir Singh (2014), Kautilya: The True Founder of Economics, Vitasta Publishing Pvt.Ltd, ISBN 978-81-925354-9-4

Radhakrishnan Pillai has written a number of books related to Chanakya — “Chanakya in the Classroom: Life Lessons for Students”, "Chanakya Neeti: Strategies for Success", "Chanakya in You", "Chanakya and the Art of War", "Corporate Chanakya", "Corporate Chanakya on Management" and "Corporate Chanakya on Leadership".