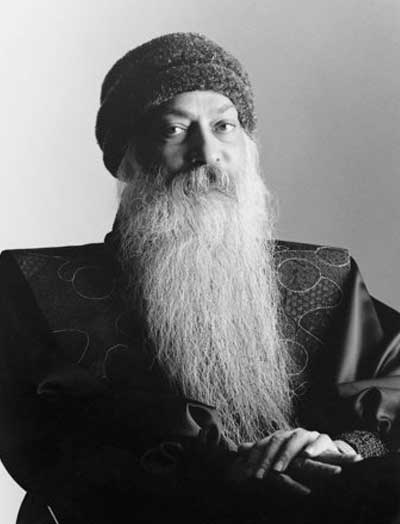

Osho

Osho

(Age 58 Yr. )

Personal Life

| Education | M.A. Philosophy |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Profession | Mystic, Spiritual Teacher and Leader of The Rajneesh Movement |

| Place | Kuchwada, Bhopal State, British India, |

Physical Appearance

| Height | 5 feet 5 inches |

| Eye Color | Black |

| Hair Color | Semi-bald |

Family Status

| Parents | Father- Babulal Jain Mother- Saraswati Bai Jain |

| Marital Status | Single |

| Siblings | Brothers- Vijay Kumar Khate, Shailendra Shekhar, Amit Mohan Khate, Aklank Kumar Khate, Niklank Kumar Jain |

Favourite

| Color | Red |

| Food | Sabudana khichdi, Dahi Vada |

| Actor | Vinod Khanna |

Index

| 1. Teachings |

| 2. Ego and the mind |

| 3. Meditation |

| 4. Sannyas |

| 5. Renunciation and the “New Man” |

| 6. Osho’s “Ten Commandments” |

| 7. Legacy |

Osho born Chandra Mohan Jain, and also known as Acharya Rajneesh from the 1960s onwards, as Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh during the 1970s and 1980s and as Osho from 1989, was an Indian mystic, guru, and spiritual teacher who garnered an international following.

A professor of philosophy, he traveled throughout India in the 1960s as a public speaker. His outspoken criticism of socialism, Mahatma Gandhi and institutionalized religions made him controversial. He also advocated a more open attitude towards sexuality: a stance that earned him the sobriquet “sex guru”in the Indian and later international press. In 1970, Osho settled for a while in Bombay. He began initiating disciples (known as neo-sannyasins) and took on the role of a spiritual teacher. In his discourses, he reinterpreted writings of religious traditions, mystics, and philosophers from around the world. Moving to Poona in 1974, he established an ashram that attracted increasing numbers of Westerners. The ashram offered therapies derived from the Human Potential Movement to its Western audience and made news in India and abroad, chiefly because of its permissive climate and Osho’s provocative lectures. By the end of the 1970s, there were mounting tensions with the Indian government and the surrounding society.

[pull_quote_right]I don’t have any biography. And whatsoever is thought to be biography is utterly meaningless.

On what date I was born, in what country I was born, does not matter. What matters is what I am now, right here.[/pull_quote_right]

In 1981, Osho relocated to the United States and his followers established an intentional community, later known as Rajneeshpuram, in the state of Oregon. Within a year, the leadership of the commune became embroiled in a conflict with local residents, primarily over land use, which was marked by hostility on both sides. The large collection of Rolls-Royce automobiles purchased for his use by his followers also attracted notoriety. The Oregon commune collapsed in 1985 when Osho revealed that the commune leadership had committed a number of serious crimes, including a bioterror attack (food contamination) on the citizens of The Dalles.

He was arrested shortly afterwards and charged with immigration violations. Osho was deported from the United States in accordance with a plea bargain. Twenty-one countries denied him entry, causing Osho to travel the world before returning to Poona, where he died in 1990. His ashram is today known as the Osho International Meditation Resort. His syncretic teachings emphasize the importance of meditation, awareness, love, celebration, courage, creativity and humor—qualities that he viewed as being suppressed by adherence to static belief systems, religious tradition and socialization. Osho’s teachings have had a notable impact on Western New Age thought, and their popularity has increased markedly since his death.

Teachings

Osho’s teachings, delivered through his discourses, were not presented in an academic setting, but interspersed with jokes and delivered with a rhetoric that many found spellbinding. The emphasis was not static but changed over time: Osho reveled in paradox and contradiction, making his work difficult to summarize. He delighted in engaging in behavior that seemed entirely at odds with traditional images of enlightened individuals; his early lectures in particular were famous for their humour and their refusal to take anything seriously. All such behavior, however capricious and difficult to accept, was explained as “a technique for transformation” to push people “beyond the mind.”

He spoke on major spiritual traditions including Jainism, Hinduism, Hassidism, Tantrism, Taoism, Christianity, Buddhism, on a variety of Eastern and Western mystics and on sacred scriptures such as the Upanishads and the Guru Granth Sahib. The sociologist Lewis F. Carter saw his ideas as rooted in Hindu advaita, in which the human experiences of separateness, duality and temporality are held to be a kind of dance or play of cosmic consciousness in which everything is sacred, has absolute worth and is an end in itself. While his contemporary Jiddu Krishnamurti did not approve of Osho, there are clear similarities between their respective teachings.

Osho also drew on a wide range of Western ideas. His view of the unity of opposites recalls Heraclitus, while his description of man as a machine, condemned to the helpless acting out of unconscious, neurotic patterns, has much in common with Freud and Gurdjieff. His vision of the “new man” transcending constraints of convention is reminiscent of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil; his views on sexual liberation bear comparison to D. H. Lawrence; and his “dynamic” meditations owe a debt to Wilhelm Reich.

Ego and the mind

According to Osho every human being is a Buddha with the capacity for enlightenment, capable of unconditional love and of responding rather than reacting to life, although the ego usually prevents this, identifying with social conditioning and creating false needs and conflicts and an illusory sense of identity that is nothing but a barrier of dreams. Otherwise man’s innate being can flower in a move from the periphery to the center.

Osho views the mind first and foremost as a mechanism for survival, replicating behavioural strategies that have proven successful in the past. But the mind’s appeal to the past, he said, deprives human beings of the ability to live authentically in the present, causing them to repress genuine emotions and to shut themselves off from joyful experiences that arise naturally when embracing the present moment: “The mind has no inherent capacity for joy. … It only thinks about joy.” The result is that people poison themselves with all manner of neuroses, jealousies and insecurities. He argued that psychological repression, often advocated by religious leaders, makes suppressed feelings re-emerge in another guise, and that sexual repression resulted in societies obsessed with sex. Instead of suppressing, people should trust and accept themselves unconditionally. This should not merely be understood intellectually, as the mind could only assimilate it as one more piece of information: instead meditation was needed.

Meditation

Osho presented meditation not just as a practice but as a state of awareness to be maintained in every moment, a total awareness that awakens the individual from the sleep of mechanical responses conditioned by beliefs and expectations. He employed Western psychotherapy in the preparatory stages of meditation to create awareness of mental and emotional patterns.

He suggested more than a hundred meditation techniques in total. His own “Active Meditation” techniques are characterized by stages of physical activity leading to silence. The most famous of these remains Dynamic Meditation, which has been described as a kind of microcosm of his outlook. Performed with closed or blindfolded eyes, it comprises five stages, four of which are accompanied by music. First the meditator engages in ten minutes of rapid breathing through the nose. The second ten minutes are for catharsis: “Let whatever is happening happen. … Laugh, shout, scream, jump, shake—whatever you feel to do, do it!” Next, for ten minutes one jumps up and down with arms raised, shouting Hoo! each time one lands on the flat of the feet. At the fourth, silent stage, the meditator stops moving suddenly and totally, remaining completely motionless for fifteen minutes, witnessing everything that is happening. The last stage of the meditation consists of fifteen minutes of dancing and celebration.

Osho developed other active meditation techniques, such as the Kundalini “shaking” meditation and the Nadabrahma “humming” meditation, which are less animated, although they also include physical activity of one sort or another. His later “meditative therapies” require sessions for several days, OSHO Mystic Rose comprising three hours of laughing every day for a week, three hours of weeping each day for a second, and a third week with three hours of silent meditation. These processes of “witnessing” enable a “jump into awareness”. Osho believed such cathartic methods were necessary, since it was difficult for modern people to just sit and enter meditation. Once the methods had provided a glimpse of meditation people would be able to use other methods without difficulty.

Sannyas

Another key ingredient was his own presence as a master; “A Master shares his being with you, not his philosophy. … He never does anything to the disciple.” The initiation he offered was another such device: “… if your being can communicate with me, it becomes a communion. … It is the highest form of communication possible: a transmission without words. Our beings merge. This is possible only if you become a disciple.” Ultimately though, as an explicitly “self-parodying” guru, Osho even deconstructed his own authority, declaring his teaching to be nothing more than a “game” or a joke. He emphasized that anything and everything could become an opportunity for meditation.

Renunciation and the “New Man”

Osho saw his “neo-sannyas” as a totally new form of spiritual discipline, or one that had once existed but since been forgotten. He felt that the traditional Hindu sannyas had turned into a mere system of social renunciation and imitation. He emphasized complete inner freedom and the responsibility to oneself, not demanding superficial behavioural changes, but a deeper, inner transformation. Desires were to be accepted and surpassed rather than denied. Once this inner flowering had taken place, desires such as that for sex would be left behind.

Osho said that he was “the rich man’s guru” and that material poverty was not a genuine spiritual value. He had himself photographed wearing sumptuous clothing and hand-made watches and, while in Oregon, drove a different Rolls-Royce each day – his followers reportedly wanted to buy him 365 of them, one for each day of the year. Publicity shots of the Rolls-Royces were sent to the press. They may have reflected both his advocacy of wealth and his desire to provoke American sensibilities, much as he had enjoyed offending Indian sensibilities earlier.

Osho aimed to create a “new man” combining the spirituality of Gautama Buddha with the zest for life embodied by Nikos Kazantzakis’ Zorba the Greek: “He should be as accurate and objective as a scientist … as sensitive, as full of heart, as a poet … [and as] rooted deep down in his being as the mystic.” His term the “new man” applied to men and women equally, whose roles he saw as complementary; indeed, most of his movement’s leadership positions were held by women. This new man, “Zorba the Buddha”, should reject neither science nor spirituality but embrace both. Osho believed humanity was threatened with extinction due to over-population, impending nuclear holocaust and diseases such as AIDS, and thought many of society’s ills could be remedied by scientific means. The new man would no longer be trapped in institutions such as family, marriage, political ideologies and religions. In this respect Osho is similar to other counter-culture gurus, and perhaps even certain postmodern and deconstructional thinkers.

Osho’s “Ten Commandments”

In his early days as Acharya Rajneesh, a correspondent once asked Osho for his “Ten Commandments”. In reply Osho noted that it was a difficult matter because he was against any kind of commandment but, “just for fun”, set out the following;

- Never obey anyone’s command unless it is coming from within you also.

- There is no God other than life itself.

- Truth is within you, do not search for it elsewhere.

- Love is prayer.

- To become a nothingness is the door to truth. Nothingness itself is the means, the goal and attainment.

- Life is now and here.

- Live wakefully.

- Do not swim—float.

- Die each moment so that you can be new each moment.

- Do not search. That which is, is. Stop and see.

Legacy

While Osho’s teachings met with strong rejection in his home country during his lifetime, there has been a change in Indian public opinion since Osho’s death. In 1991, an influential Indian newspaper counted Osho, along with figures such as Gautama Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi, among the ten people who had most changed India’s destiny; in Osho’s case, by “liberating the minds of future generations from the shackles of religiosity and conformism.” Osho has found more acclaim in his homeland since his death than he ever did while alive. Writing in The Indian Express, columnist Tanweer Alam stated, “The late Osho was a fine interpreter of social absurdities that destroyed human happiness.”

At a celebration in 2006, marking the 75th anniversary of Osho’s birth, Indian singer Wasifuddin Dagar said that Osho’s teachings are “more pertinent in the current milieu than they were ever before.”In Nepal, there were 60 Osho centres with almost 45,000 initiated disciples as of January 2008. Osho’s entire works have been placed in the Library of India’s National Parliament in New Delhi. Prominent figures such as Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and the Indian Sikh writer Khushwant Singh have expressed their admiration for Osho. The Bollywood actor and Osho disciple Vinod Khanna, who had worked as Osho’s gardener in Rajneeshpuram, served as India’s Minister of State for External Affairs from 2003 to 2004. Over 650 books are credited to Osho, expressing his views on all facets of human existence. Virtually all of them are renderings of his taped discourses. His books are available in 55 different languages and have entered best-seller lists in countries such as Italy and South Korea.

Internationally, after almost two decades of controversy and a decade of accommodation, Osho’s movement has established itself in the market of new religions. His followers have redefined his contributions, reframing central elements of his teaching so as to make them appear less controversial to outsiders. Societies in North America and Western Europe have met them half-way, becoming more accommodating to spiritual topics such as yoga and meditation. The Osho International Foundation (OIF) runs stress management seminars for corporate clients such as IBM and BMW, with a reported (2000) revenue between $15 and $45 million annually in the U.S.

Osho’s ashram in Pune has become the Osho International Meditation Resort, one of India’s main tourist attractions. Describing itself as the Esalen of the East, it teaches a variety of spiritual techniques from a broad range of traditions and promotes itself as a spiritual oasis, a “sacred space” for discovering one’s self and uniting the desires of body and mind in a beautiful resort environment. According to press reports, it attracts some 200,000 people from all over the world each year; prominent visitors have included politicians, media personalities and the Dalai Lama. Before anyone is allowed to enter the resort, an AIDS test is required, and those who are discovered to have the disease are not allowed in. In 2011, a national seminar on Osho’s teachings was inaugurated at the Department of Philosophy of the Mankunwarbai College for Women in Jabalpur. Funded by the Bhopal office of the University Grants Commission, the seminar focused on Osho’s “Zorba the Buddha” teaching, seeking to reconcile spirituality with the materialist and objective approach.